…doesn’t mean you’re in shape!”

So said my high-school cross-country coach one fine autumn day as I shirked my way through another practice and the words rang as true this past weekend as they did then. I entered myself in the “Surfers Challenge,” a foot race along the Indian Ocean coast in East London, the next big city heading southwest from Mthatha.

Employing the patented training routine I’ve used before, notably in Nome’s Stroke-n-Croak triathlon and my bike trip through Maine when I graduated from college, I did absolutely zero training for the event. (It’s all about peaking at the right time you see.) This, despite the fact that the race was longer than anything I’d ever run before, either 16- or 18-kilometers. (The race organizers never said for certain and there weren’t any distance markers along the way.) In any event, it was a long way and I was not prepared at all for it.

The course was actually quite beautiful, right along the beach, with rolling dunes on one side and pounding surf on the other. I might have enjoyed it if I hadn’t been focused on the ground directly in front of me, trying to pick my way through terrain that included sand, loose stones, and flat, wet, rocks. There were also two river crossings, with a swift current and water up to my chest. This was kind of neat, except that the first crossing was at about the 6-kilometer mark and meant I had to run with soaked shoes for the rest of the race.

Emerging from river number one.

By the end of the race, the (heavy) wet shoes and an unfortunate cramp in my quadriceps conspired to reduce my forward movement to a pathetic combination of a hobble and a stagger. I was passed by just about everyone in the race on the last stretch of coast but I finished and I didn’t once have to walk. My finishing time, though, I’ll keep to myself, lest you calculate my embarrassing split times.

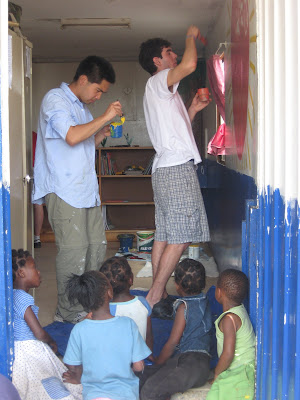

Since I was nearby, I dropped in on my fellow missionary Matt in Grahamstown and managed to get a day off work in Itipini to go to work with him and see what he does. He and I are engaged in completely different types of work but, as we found out yet again, we wrestle with many similar issues on a daily basis.

In the morning, I went with him to the school for children with disabilities that he volunteers at. The highlight was recess when the children took out the rugby ball and the cricket bat (an example of the constant reminders that I’m not at home anymore). I joined in the cricket game and I’d like to think I did all right. I managed to hit and catch the ball, though things went south when I tried to bowl. Generally speaking, you probably haven’t bowled correctly when the batsman collapses in hysterics at your flailing attempt to throw the ball instead of swinging at it.

I could never quite replicate that form.

Hilda comes to

Hilda comes to

Emerging from river number one.

Emerging from river number one.