Where do you see yourself in…?

I am sure most people in my age bracket have at some point been asked some variation of the question, “where do you see yourself in 1/5/10 years?” I’ve never had a good answer for this question because the future always looks pretty hazy to me. But I have always been clear that my time horizon is at least that long. In 10 years, I’ll be doing something even if I don’t know what it is now. And - hard as it may be to conceive right now - at some point, I might even be a retired old guy. In short, I’ve still got a lot of life left to live, with lots of things still to do. Based on life expectancy in the rich world, I can reasonably assume that right now my life is only about a third over.

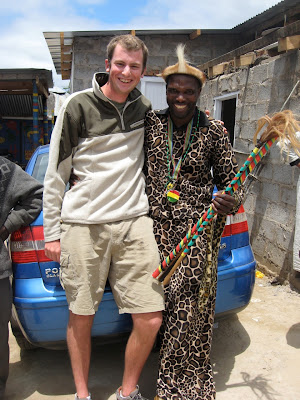

What about my good friend Noxolo, who was born and raised in Itipini? She is three months and six days younger than me, has two children, and is HIV-positive. If I asked her where she saw herself in 1/5/10 years, what would be her answer? Chances are, given the pretty constant trajectory of her life so far, that she would answer something about living in Itipini, trying to make ends meet however she can. I would like to think I could help her change that answer but given my general ineffectuality here, it’s hard to see how that would happen.

She is three months and six days younger than me, has two children, and is HIV-positive. If I asked her where she saw herself in 1/5/10 years, what would be her answer? Chances are, given the pretty constant trajectory of her life so far, that she would answer something about living in Itipini, trying to make ends meet however she can. I would like to think I could help her change that answer but given my general ineffectuality here, it’s hard to see how that would happen.

Her HIV is obviously a complicating factor. Yes, there are drugs now that prolong the life of HIV-positive people and, with a little luck, she might even be able to live indefinitely with HIV. Anti-retroviral treatment hasn’t been around long enough in South Africa to gauge its long-term effectiveness but there’s enough reason to hope based on the experience of people (e.g. Magic Johnson) in the rich world. And that’s assuming there are no further advancements in HIV treatment, an assumption I dearly hope is incorrect.

Still, when I’m honest with myself, I have to wonder if she’ll even be alive in five or ten years. There are just too many factors working against her prospects. And I’ve known too many other people my age or younger who have already died. There were some new life expectancy statistics for South Africa published recently and I think the average for a woman was 51. At the very least, that means Noxolo can reasonably assume her life is more than half over.

What a startling difference that is! Here I am at 26 and I feel my life has barely begun. Noxolo is 26 and is in the second half of her life. I have a full third as many more years to live my life as she has.

When we talk about the accident of birth - as I have - the discussion is often in terms of the opportunities we are afforded or denied by virtue of the position in society - location, social class, race, etc. - we are born into. But what about the opportunities afforded simply by having more years to fill? It seems to me the most basic of inequities.